COMMON NAME: Black rot of grapes

SCIENTIFIC NAME of causal agent: Guignardia bidwelli (anamorph Phyllosticta ampelicida)

DISEASE DESCRIPTION:

Black rot of grape is caused by the ascomycete Phyllosticta ampelicida, a fungus which is commonly referred to as Guignardia bidwelli in the scientific community [1]. In grape-growing areas which experience warm and humid conditions in the spring and early summer, this disease has the potential to significantly decrease grape yield and wine quality [1]. Typically, a rainy period followed by 2-3 days of foggy weather favors development of this disease [2].

SYMPTOMS:

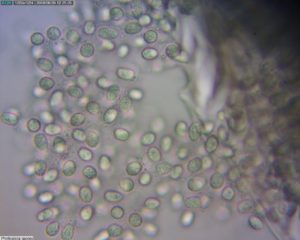

In the early stages of the leaf infection, tan-colored lesions around 2-10 mm in diameter appear on the leaf, which turn reddish-brown as they mature. Spore-bearing fruiting bodies called pycnidia appear as small black pimples (often arranged in a ring) inside the lesions (see image) [3].

On shoots, tendrils, petioles and pedicels, lesions are characterized by elongated dark colored depressions that turn black. Lesions on canes may grow only up to a quarter of the stem circumference [4]. Lesions may disrupt water and nutrient flow beyond the point of infection, resulting in tissue weakening and death [3].

Infection of berries manifests as small circular whitish spots, which progressively increase in size. When spots are around 2 mm in diameter, reddish-brown margins form. Within 24 hours, spots grow to a size of 8-9 mm, forming 2-3 dark, concentric rings. Within 7-10 days, the entire berry shrivels into a hard black body called a mummy. Pycnidia (tiny black dots) develop on the surface of the berry (see image) [4].

The disease cycle involves two types of spores, both sexual and asexual spores of the pathogen. The sexual spores called ascospores are produced in a structure known as an ascus, while the asexual spores called conidia are produced in the pycnidia. Primary infections are caused by ascospores and conidia which form in mummified berries that have overwintered in the vineyard, while secondary infections involve conidia from mummified berries and other tissues [5, 6], which are released throughout the growing season [6].

The release of ascospores from mummies (either attached to the trellis, or fallen to the ground) is triggered by spring rains, and are spread by the wind over short distances [6]. In the case of mummies that have overwintered on the ground, the release of ascospores occurs 2-3 weeks after bud break and continues up to 1-2 weeks af

BIOLOGY:

ter onset of flowering. The release period of ascospores from mummies attached to the trellis is from early pre-flowering period through veraison (onset of ripening) [6].

Conidia are dispersed by splashing rain drops. Even though mummified berries attached to the trellis are the main source of conidia, these spores can also overwinter for at least 2 years in canes and tendrils. While conidia from mummies attached to the trellis are dispersed from early pre-flowering period through veraison, ones from cane lesions are dispersed from bud break through mid-summer [6].

The dispersed spores germinate on fresh plant parts, which results in infection and continued disease.

MANAGEMENT METHODS:

Sanitation is an essential control strategy for this disease. As mummified berries are capable of releasing large numbers of spores which can germinate on and infect nearby susceptible tissue, the mummies must be removed from the vineyard and destroyed during dormant pruning. Alternatively, they can be buried with cultivation before bud break after being dropped to the vineyard ground [3].

Preventive measures include application of fungicides and planting of resistant varieties [2]. Additionally, proper design of vineyards and canopy measurement aimed at improving airflow through the canopy would facilitate better control of the disease by decreasing fruit and foliage drying times post rain, and increasing fungicide spray penetration [3].

RESOURCE LINKS:

[1]. Onesti, G., González-Domínguez, E., Manstretta, V., and Rossi, V. 2018. Release of Guignardia bidwellii ascospores and conidia from overwintered grape berry mummies in the vineyard: Inoculum release of Guignardia bidwellii. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 24:136–144. Website: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ajgw.12321?casa_token=6aknhurs4V4AAAAA:ePIo4S3BT9mIXRTlFM3V_ZBbLXAgGBMuKg9ESJG4nh2Kvn_kI6aEcTwlbwUZKz2ls2D_SP5pOTFmqQ

[2] Grape. n.d. Texas Plant Disease Handbook. Texas A&M Agrilife Extension.

https://plantdiseasehandbook.tamu.edu/food-crops/fruit-crops/grape/

[3] Diseases of the Grapevine: Black Rot. n.d. Texas A&M Viticulture & Biology. https://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/vitwine/viticulture/viticulture-resources/httpaggie-horticulture-tamu-eduvitwineviticultureviticulture-resourceshttpaggie-horticulture-tamu-eduvitwineviticultureviticulture-resourcesimage-gallery-of-grapevine-diseasesdiseases-of-the-g/diseases-of-the-grapevine-black-rot/

[4] Miller, J. W. 1968. Black Rot of Grape. Plant Pathology Circular No. 76. Florida Department of Agriculture Division of Plant Industry. https://www.fdacs.gov/content/download/11083/file/pp76.pdf

[5] Hoffman, L. E., Wilcox, W. F., Gadoury, D. M., Seem, R. C., and Riegel, D. G. 2004. Integrated Control of Grape Black Rot: Influence of Host Phenology, Inoculum Availability, Sanitation, and Spray Timing. Phytopathology. 94:641–650. Website:

https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.6.641

[6] Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics. 2017. National Diagnostic Protocol for Phyllosticta ampelicida – NDP13 V2. (Eds. Subcommittee on Plant Health Diagnostics) Author Sosnowski, M and Tan, Y-P; Reviewers de Alwis, S.K., Tan, Y-P. and Baskarathevan, J. ISBN 978-0-9945113-7-9. Commonwealth of Australia Department of Agriculture and Water Resources. Website: https://www.plantbiosecuritydiagnostics.net.au/app/uploads/2018/11/NDP-13-Black-rot-on-grapevine-Phyllosticta-ampelicida-V2.pdf

This factsheet is authored by

Manjari Mukherjee

pursuing a PhD in Plant Pathology

Factsheet information for the plant health issues represented by the images on the 2020 TPDDL calendar were written by graduate students enrolled in the Department of Plant Pathology & Microbiology DR. DAVID APPEL’s Graduate level Introductory Plant Pathology course (PLPA601) in the 2019 Fall semester. This exercise provides an opportunity for a high impact learning activity where the students are tasked with producing an informational output directed to the general public. This activity provides an opportunity for the students to write and produce a (hopefully) useful product to communicate information on plant health issues to the public.